The entry on apparent and absolute magnitude left two (related) questions unanswered.

- How do we find the distance to a star?

- What is a parsec?

You might also be wondering if learning the luminosity of a star is worth doing logarithms. The answer to that is yes, because knowing the luminosity of many stars led us to our modern understanding of stars – how they’re formed, how long they last, and how they end. And we rely on that understanding of stars to learn about almost everything else in the Universe.

To learn about distances and parsecs, be sure that you’ve watched the Crash Course video on distances. To review, you can start around 4:00, when Phil introduces the Astronomical Unit.

To use parallax, we need some technical notes to accompany the concept.

The first is units. The most common unit of angle in astronomy is degrees; there are 360 degrees in a full circle of arc. Each degree is broken down into 60 arcminutes, and each arcminute is broken down into 60 arcseconds. These are the same units used to specify declination when mapping the sky or azimuth and elevation with locating an object above the horizon.

Degrees, arcminutes, and arcseconds are used to measure angular sizes, angular separations, and angular resolution. In parallax, the important concept is angular separation. When a star’s location in the sky shifts, there is an angular separation between its initial and final locations. You can think of the star moving, a tiny bit, on the celestial sphere. That shift is measured in arcseconds.

The second concept is the relationship between distance and parallax. Stars that are further away have a smaller parallax. This is what Phil was demonstrating by moving his thumb closer to and further from his face.

You can see this in the screen shot from the Crash Course video. When we talk about the parallax of a star, the baseline is always the Earth’s orbit around the Sun; this makes the base of a triangle. The star is at the tip of the triangle, and the parallax is the angle indicated in the diagram. The larger the distance between the Sun and the Earth, the skinnier the triangle, and the smaller the parallax angle. (See if you can imaging the triangle stretching out as you pull the star further away.)

If you do the geometry, then it turns out that the distance and the parallax are inversely proportional to each other. This means that if the distance to a star doubles, then the parallax angle will halve. And vice versa, halving the distance to a star would double its parallax angle. (If you like geometry, and want to do it yourself, know that this relies on using the small angle approximation for sine. The parallax of a star is always very small, less than one arcsecond.)

We’re almost done with parallax; the last piece is the parsec. A parsec is a measure of distance (not time). The par in parsec comes from parallax, the sec in parsec comes from arcsecond (which is a measure of angle, not time). If a star were one parsec away (which unfortunately none are), then its parallax would be one arcsecond. All stars are actually further away than 1 parsec (the closest is 1.3 parsecs away) and have parallaxes of less than one arcsecond.

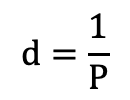

Finally, let’s put it in a formula. The relationship between parallax and distance is…

where d is the distance (measured in parsecs) and P is the parallax (measured in arcseconds).

Entries in this Series (Stellar Properties)

Magnitude and Parallax

- Bright Stars – Luminous or Nearby

- A Brief Introduction to the Magnitude System

- Apparent and Absolute Magnitude

- Parallax

Luminosity and Size